The French Huguenots to America

The HUGUENOTS to America became Cannibals in the End

Prologue.

The religious persecutions across Europe drove people out of France. Spain led the tyranny of monks and inquisitors, along with their swarms of spies and informers, their racks, dungeons, and fagots, all of which crushed all freedom of thought or speech.

The Reform prompted thousands of people to leave their homes, and this fact in itself is a good reason for the researcher to dig deeply into the historical past.

While the persecuted sought solace in other regions of the world, we should seek information concerning the resulting voyages upon the high seas. Had all of the ships’ logs survived, we would have information as to the names, ages, and places of deportation. What a sweet dream if that were to be true! Thousands upon thousands of ships had taken to the seas with its congregations of persecuted citizens by the mid fifteen hundreds, and the evidence lies on the ocean floor. No one, not even historians, can possibly calculate the innumerable losses.

Thus, any evidence at concerning the movements of our ancestors is valuable.

The names mentioned here were found in the book of Francis Parkman (listed as a source) and were included as a possible interest to historians and genealogists.

1550–1558

The old palace of the Louvre, reared by the “Roi Chevalier” on the site of those dreary feudal towers which of old had guarded the banks of the Seine River, held within its sculptured masonry the worthless brood of corrupt and factious nobles, bishops and cardinals who contended around the sickbed of the futile king.

Catherine de Medicis, with her stately form, her mean spirit, her bad heart, and her fathomless depths of duplicity, strove by every subtle art to hold the balance of power among them. The bold, pitiless, insatiable Guise, and his brother the Cardinal of Lorraine, the incarnation of falsehood, rested their ambition on the Catholic party.

Their army was a legion of priests, and the black swarms of countless monasteries, who by the distribution of alms held in pay the rabble of cities and starving peasants on the lands of impoverished nobles. Montmorency, Conde, and Navarre leaned towards the Reform, — doubtful and inconstant chiefs, whose faith weighed light against their interests. Yet, amid vacillation, selfishness, weakness, and treachery, one great man was like a tower of trust, and this was Gaspar de Coligny.

Firm in his convictions, steeled by perils and endurance, calm, sagacious, resolute, grave even to severity, a valiant and redoubted soldier, Coligny looked abroad on the gathering storm and read its danger in advance. He saw a strange depravity of manners; bribery and violence overriding justice; discontented nobles, and peasants ground down with taxes.

In the midst of this rottenness, the Calvinistic churches, patient and stern, were fast gathering to themselves the better life of the nation. Among and around them tossed the surges of clerical hate. Luxurious priests and libertine monks saw their disorders rebuked by the grave virtues of the Protestant zealots. Their broad lands, their rich endowments, their vessels of silver and of gold, their dominion over souls, — in itself a revenue, — were all imperiled by the growing heresy. The storm was thickening, and it must burst soon.

Enter Nicolas Durand de Villegagnon, a Moorish cavalier who rushed into the camp of Emperor Charles the Fifth at Algiers, and pierced his arm with a lance. Afterward, Villegagnon with six followers, all friends of his own, passed under cover of night through the infidel leaguer, climbed the walls by ropes lowered from above, took command, repaired the shattered towers with his own hands, and animated the garrison to resistance so stubborn that the besiegers lost heart and betook themselves to their galleys. Villegagnon was an able and accomplished mariner, scholar, and linguist, with a commanding presence of eloquence and persuasion.

And, he claimed himself as a protestant. Disgusted at home, his fancy crossed the seas. He aspired to build for France and himself an empire amid the tropical splendors of Brazil.

Coligny spoke of an asylum for persecuted religions, a Geneva in the wilderness, far from priests and monks and Francis of Guise.

The Admiral of France gave him a ready ear; if, indeed, he himself had not first conceived the plan. Yet to the King, an active burner of Huguenots, Coligny too urged it as an enterprise, not for the Faith, but for France. In secret, Geneva was made privy to it, and Calvin himself embraced it with zeal. The enterprise, in fact, had a double character, political as well as religious. It was the reply of France, the most emphatic she had yet made, to the Papal bull which gave all the western hemisphere to Portugal and Spain; and, as if to point her answer, she sent, not Frenchmen only, but Protestant Frenchmen, to plant the fleur-de-lis on the shores of the New World.

Two vessels.

Two vessels were made ready, in the name of the King. The body of the emigration was Huguenot, mingled with young nobles, restless, idle, and poor, with reckless artisans, and piratical sailors from the Norman and Breton seaports. They were put to sea from Havre on the twelfth of July, 1555, and early in November saw the shores of Brazil. Entering the harbor of Guanabara, Villegagnon landed men and stores on an island, built huts, and threw up earthworks for Fort Coligny.

Rio Janeiro (formerly Guanabara)

Villegagnon signalized his newborn Protestantism by an intolerable solicitude for the manners and morals of his followers. The whip and the pillory required the least offense. The wild and discordant crew, starved and flogged for a season into submission, conspired at length to rid themselves of him; but while they debated whether to poison him, blow him up, or murder him and his officers in their sleep, three Scotch soldiers, probably Calvinists, revealed the plot, and the vigorous hand of the commandant crushed it in the bud.

But the mainland was infested with hostile tribes, and threatened by the Portuguese, who regarded the French occupancy as a violation of their domain.

Meanwhile, in France, Huguenot influence, aided by ardent letters sent home by Villegagnon in the returning ships, was urging the new society of Huguenots on the island.

A second voyage was sent to Rio Janeiro of some 290 persons in three vessels

Most of the emigrants were Huguenots. Geneva sent a large deputation and among them several ministers, full of zeal for their land of promise and their new church in the wilderness. There were five young women, also, with a matron to watch over them.

They were no sooner on the high seas than the piratical character of the Norman sailors, in no way exceptional at that day, began to declare itself. They hailed every vessel weaker than themselves, pretended to be short of provisions, and demanded leave to buy them; then, boarding the stranger, plundered her from stem to stern.

After a passage of four months, on the ninth of March, 1557, they entered the port of Guanabara (Rio Janeiro) and saw the fleur-de-lis floating above the walls of Fort Coligny.

The ships fired cannons as a salute, and the vessels, crowded with sea-worn emigrants, moved towards the landing.

Villegagnon presented himself in the picturesque attire which marked the warlike nobles of the period and came down to the shore to greet the ministers of Calvin. With hands uplifted and eyes raised to heaven, he bade them welcome to the new asylum of the faithful; then launched into a long harangue full of zeal and unction.

His discourse finished, and he led the way to the dining hall where meager provisions of dried fish and rainwater awaited their appetites.

Among the emigrants was a student of the Sorbonne, with whom and the ministers arose a fierce and unintermittent war of words. The disputes between the ministers and the students continued.

Villegagnon took part with the student, and between them, they devised a new doctrine, abhorrent like to Geneva and to Rome. The advent of this nondescript heresy was the signal of redoubled strife. The dogmatic stiffness of the Geneva ministers chafed Villegagnon to fury. He felt himself, too, in a compromised position. He feared the court.

There were Catholics in the colony who might report him as an open heretic. On this point his doubts were set at rest; for a ship from France brought him a letter from the Cardinal of Lorraine, couched, it is said, in terms which restored him forthwith to the bosom of the Church. Villegagnon now affirmed that he had been deceived in Calvin, and pronounced him a “frightful heretic.” He became despotic beyond measure and would bear no opposition. As a result, the ministers were reduced nearly to starvation and found themselves under a tyranny worse than that from which they had fled.

At length, he drove them from the fort and forced them to bivouac on the mainland, at the risk of being butchered by Indians, until a vessel loading with Brazil woodin the harbor should be ready to carry them back to France.

Having rid himself of the ministers, he caused three of the more zealous Calvinists to be seized, dragged to the edge of a rock, and thrown into the sea. A fourth, equally obnoxious, but who, being a tailor, could ill be spared, was permitted to live on condition of recantation. Then, mustering the colonists, he warned them to shun the heresies of Luther and Calvin.

Desperation

Meanwhile, the banished ministers drifted slowly into stormy seas, their provisions failed, and their water casks were empty. In their famine, they chewed the Brazil wood with which the vessel was laden, devoured every scrap of leather, ate the horn of lanterns, hunted rats through the hold, and sold them to each other at enormous prices. At length, stretched on the deck, sick, listless, attenuated, and scarcely able to move a limb, they finally approached a faint cloud-like line that marked the coast of Brittany.

If they thought that their perils were ended, they were mistaken, for one of them, Jean de Lery bore a sealed letter from Villegagnon to the magistrates of the first French port at which they might arrive. It denounced them as heretics, worthy to be burned. But the magistrates leaned towards the Reform, and the passengers were spared.

So what happened to the little colony?

Before the year 1558 had ended, Guanabara (Rio Janeiro) fell prey to the Portuguese. They battered down the fort, and slew the feeble garrison. Spain and Portugal made good their claim to the vast domain, the mighty vegetation, and undeveloped riches of a land Villegagnon called “Antarctic France.”

1562, 1563. A Second Huguenot Colony

JEAN RIBAUT.

In the year 1562 as a cloud of black and deadly portent was thickening over France, a second Huguenot colony sailed for the New World. The calm, stern man who represented and led the Protestantism of France felt to his inmost heart the peril of the time. Jean Ribaut would fain build up a city of refuge for the persecuted sect.

Gaspar de Coligny, too high in power and rank to be openly assailed, was compelled to act with caution. He must act, too, in the name of the Crown, and in virtue of his office of Admiral of France. A nobleman and a soldier, His scheme promised a military colony, not a free commonwealth. The plan was to establish a Huguenot colony in America.

Havre. 18 February 1562

An excellent seaman and stanch Protestant, Jean Ribaut of Dieppe, commanded the expedition. Under him, besides sailors, were a band of veteran soldiers, and a few young nobles. They crossed the Atlantic, and on the thirtieth of April, in the latitude of twenty-nine and a half degrees, saw the long, low lines of the Florida wilderness.

French Cape, a headland of the Mantazas Inlet

On the next morning, the first of May, they found themselves off the mouth of a great river. No doubt, this was St. John’s River (which they named St. May River).

Riding at anchor on a sunny sea, they lowered their boats, crossed the bar that obstructed the entrance, and floated on a basin of deep and sheltered water, “boiling and roaring,” says Ribaut, “through the multitude of all kinds of fish.”

Indians were running along the beach, and out upon the sandbars, beckoning them to land. They pushed their boats ashore and disembarked, — sailors, soldiers, and eager young nobles. Corselet and morion, arquebuse and halberd, flashed in the sun that flickered through innumerable leaves, as, kneeling on the ground, they gave thanks to God, who had guided their voyage to an issue full of promise. The Indians, seated gravely under the neighboring trees, looked on in silent respect, thinking that they worshipped the sun. “They be all naked and of a goodly stature, mighty, and as well shapen and proportioned of the body as any people in ye world; and the fore part of their body and arms be painted in Azure, red, and black, so well and so properly as the best Painter of Europe could not amende it.” With their squaws and children, they presently drew near, and, strewing the earth with laurel boughs, sat down among the Frenchmen. Their visitors were much pleased with them, and Ribaut gave the chief, whom he calls the king, a robe of blue cloth, worked in yellow with the regal fleur-de-lis.

Apparently, the Huguenots from this voyage settled in the St. Augustine area. There is evidence of their existence in the cemetery. While there, the Huguenot cemetery was locked to visitors and although I attempted to read the tombstones, but the french inscriptions were rotted in age.

At some point, Ribaut left the St. Augustine region and sailed north towards Port Royal, South Carolina.

Although the town of Port Royal on Beaufort Island was not established until 1874, there was a port there during the late 1500s, because there is a record of the Huguenots landing there on 27 May 1562. They saw a stream which they named Lilbourne (probably Skull Creek) and a wide river (probably the Beaufort). By the time they landed, the Indians had fled.

Charlesfort

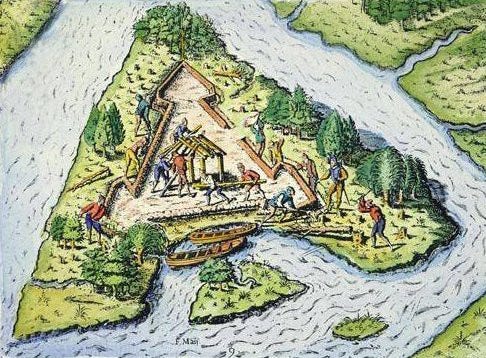

A fort was begun on a small stream called the Chenonceau, probably Archer’s Creek, about six miles from the site of Beaufort. They named it Charlesfort, in honor of the unhappy son of Catherine de Medicis, Charles the Ninth, the future hero of St. Bartholomew. Ammunition and stores were sent on shore, and on the eleventh of June, with his diminished company, Ribaut returned to France.

It is said that the Huguenot settleers visited the villages of five petty chiefs, whom they called kings, feasting everywhere on hominy, beans, and game, and loaded with gifts. One of these chiefs, named Audusta, invited them to the grand religious festival of his tribe. When they arrived, they found the village alive with preparation, and troops of women busied in sweeping the great circular area where the ceremonies were to take place. But as the noisy and impertinent guests showed a disposition to undue merriment, the chief shut them all in his wigwam, lest their Gentile eyes should profane the mysteries. Here, immured in darkness, they listened to the howls, yelpings, and lugubrious songs that resounded from without. One of them, however, by some artifice, contrived to escape, hid behind a bush, and saw the whole solemnity, — the procession of the medicinemen and the bedaubed and befeathered warriors; the drumming, dancing, and stamping; the wild lamentation of the women as they gashed the arms of the young girls with sharp mussel-shells, and flung the blood into the air with dismal outcries. A scene of ravenous feasting followed, in which the French, released from durance, were summoned to share.

After the carousel, they returned to Charlesfort. The Indians brought them supplies as long as their own lasted, but the harvest was not yet ripe, and their means did not match their goodwill. To the south, there were two kings, Ouade and Couexis, who were rich beyond belief in maize, beans, and squashes and fed the colonists. The colonists returned to Charlesfort rejoicing, but that night the storehouse caught fired and burned to the ground, along with the newly acquired stock.

It was not the generous Indian tribes who caused the end of Charles fort, but rather quarreling landsmen and sailors. Albert, a rude soldier, became violent and hanged with his own hands a drummer who had fallen under his displeasure, and banished another soldier, named La Chore, to a solitary island, three leagues from the fort where he was left to starve.

Thereafter, Nicolas Barre, a man of merit, took the command, and thenceforth there was peace. However, the distraught settlers yearned to return to France. So, once again, they set sail for France.

The Indians had kindly crafted a boat for the Frenchmen, but it was not sea-worthy. Their supplies gave out. Twelve kernels of maize a day were each man’s portion; then the maize failed, and they ate their shoes and leather jerkins. The water barrels weredrained, and they tried to slake their thirst with brine. Several died, and the rest, giddy with exhaustion and crazed with thirst, were forced to ceaseless labor, bailing out the water that gushed through every seam. Headwinds set in, increasing to a gale, and the wretched brigantine, with sails close-reefed, tossed among the savage billows at the mercy of the storm. A heavy sea rolled down upon her and burst the bulwarks on the windward side. The surges broke over her, and, clinging with desperate grip to spars and cordage, the drenched voyagers gave up all for lost. At length she righted. The gale subsided, the wind changed, and the crazy, water-logged vessel again bore slowly towards France.

Gnawed with famine, they counted the leagues of the barren ocean that still stretched before, and gazed on each other with haggard wolfish eyes, till a whisper passed from man to man that one, by his death, might ransom all the rest. The lot was cast, and it fell on La Chore, the same wretched man whom Albert had doomed to starvation on a lonely island. They killed him, and with ravenous avidity portioned out his flesh. The hideous repast sustained them till the land rose in sight, when, it is said, in a delirium of joy, they could no longer steer their vessel, but let her drift at the will of the tide. A small English bark bore down upon them, took them all on board, and, after landing the feeblest, carried the rest prisoners to Queen Elizabeth.

Thus closed another of those scenes of woe whose lurid clouds are thickly piled around the stormy dawn of American history.

Comments: St. Augustine, Florida was settled by the Spanish (from Cuba) during the mid fifteen hundreds. Castillo San Marcos fort was first constructed somewhere in the mid fifteen hundreds and was later re-enforced so that the cannon balls projected by General Oglethorpe against the fort ca 1738, failed. To this day, this fort is considered impenetrable!

Settlers from England, France, Portugal, and Spain inhabited St. Augustine. The Spanish Commander, Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, was responsible for driving the Huguenots further north.

Pioneers Of France In The New World: France

and England in North America, Part First, by Francis Parkman, Jr.