If you are tracing families who went west into Alabama and Mississippi, it might be helpful to know the history of what drove them there and the routes that they took.

During the latter half of the seventeenth century, England was developing the spinning and weaving machinery which played a large part in bringing about the Industrial Revolution.

The Cotton Gin

The increased demand for raw cotton which resulted from this development was answered in 1793 by Whitney's invention of the cotton gin. Until this time, it was necessary to separate the lint from the seed by hand or by means of a pair of simple rollers. The black seeded sea island, or long staple, cotton was the only variety amenable to such processes, for its long fiber did not cling closely to the seed and could be removed easily. The short staple of the green-seeded variety clung so closely to the seed that it could not be removed profitably by these simple processes in use.

Long staple cotton could be raised only in the tidewater regions. The coast and sea islands of Georgia and South Carolina produced practically all the American output.

The short-staple cotton, on the other hand, could be raised in the uplands, and when the invention of the cotton gin rendered the culture of this variety profitable, the Georgia and South Carolina piedmont supplanted the tidewater as the principal cotton-producing area. This region had been settled by men largely from Virginia and Pennsylvania.

The culture of tobacco had pretty much worn out the land, so when upland cotton was introduced it quickly came to predominate. Towns founded for the warehousing and inspection of tobacco were abandoned because their facilities were no longer necessary. Such a town was Petersburg, at the confluence of the Broad with the Savannah Rivers, the removal of whose inhabitants went to Madison County Alabama.

That the spread of the culture of cotton into the Southwest was inevitable, is indicated by its early introduction into Mississippi Territory. For a time, this natural movement was interrupted by the War of 1812. England had been cut off from her source of supply during this war and the price of the staple went to an abnormal level, while in America, the price fell sharply. When peace was made and normal trade relations were resumed with the lifting of the blockade of our coast, England again obtained her supply of American cotton and the price in this country rose immediately. The average price of cotton for 1815 was almost thirty cents a pound!

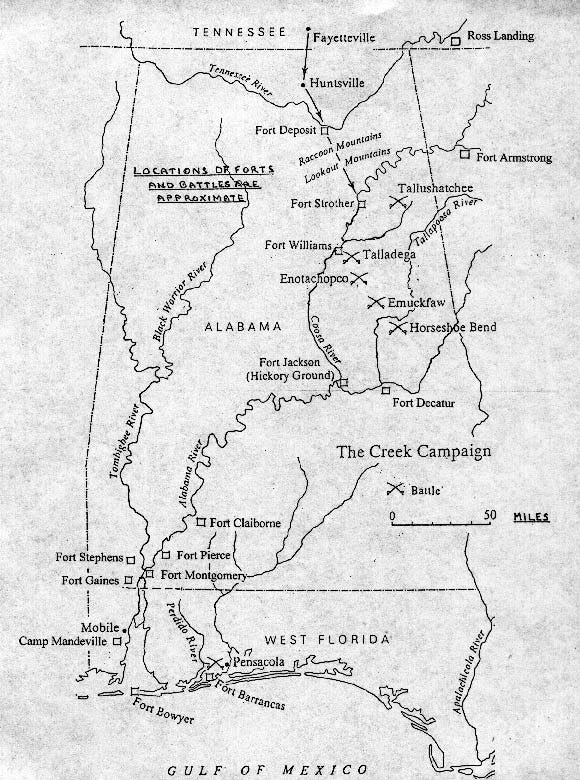

During the War of 1812, the Southern States pushed the Creek Indian tribes further westward, with the major conflict ending in Alabama. Now, Georgians, who had once entered the territory with written permission from the Governor of Georgia, began trickling towards the abandoned villages.

The need for new lands to raise cotton crops drove immigrants through the old Indian territory. The result was that over a hundred thousand acres were disposed of by the government. In 1815, the sale of newly surveyed land was opened at St. Stephens, but no sales were made in the new Creek cession until 1817 when three-quarters of a million dollars worth of these lands were sold!.

The old Georgia-South Carolina piedmont region had two distinct disadvantages from the point of view of the cotton planter. Its soil was not considered so fertile as that of the Alabama river bottoms and prairies; and it lacked transportation facilities, being cut off from the tidewater by the broad pine barrens, and being without navigable rivers.

The tidewater had its staple crops of tobacco, rice, and sea-island cotton, which were not disturbed by the newly developing cotton crop in Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi.

The Poor Farmer's Trek into Alabama and Mississippi

Few people of extensive wealth moved into the Alabama region during the period of early settlement. Only the man who needed to better his fortune had an inducement to make the necessary sacrifice. Those who had slaves usually owned but a small number and many who later became planters had no slaves at all, to begin with. In other words, the small farmer of the piedmont region became the pioneer planter of the Southwest.

When a man prepared to transplant his establishment, he usually sold the land he held and retained the proceeds for the purchase of his new domain. His household goods and farm implements were packed on wagons and started out on the rough road toward the new home. The slaves drove the herds of cattle and hogs, while the planter's family brought up the rear in a carriage. It was a tedious journey, the roads being merely clearings through the forest, and without bridges. The smaller streams were forded and crude ferries were established at the larger ones.

Having reached the place where he was to make his home, the planter constructed a log cabin in the usual manner. Two rooms were built opposite each other and joined by a passageway. Chimneys built of stones or clay-daubed sticks were put up at opposite ends of the structure and great open hearths served for both heating and cooking. A "lean-to" might be attached behind one or both of the rooms, and an attic might be constructed above. Before the introduction of sawmills, the floors were made of puncheons, or logs split into halves, with the flat side upward. The chinks between the logs were filled with clay; the doors and shutters were of cradleboards, and the shingles were hand-split. In such a dwelling, the planter who brought his household furnishings could establish a kind of rude comfort, which sufficed even the wealthiest immigrants during the first few years of their sojourn. The first and only governor of Alabama Territory lived in such a log cabin during the years of his administration and until his premature death.

From 1815 onward, families poured into the ceded lands and "squatted" upon them in spite of the law and the Government." It was the policy of the United States to prevent intrusion until surveys could be made and the lands offered for sale at auction. Attempts were made to remove the squatters; the troops were called in and ordered to burn the cabins of those who refused to leave, but it was all of no avail.^o Men of this class, being improvident by nature, did not come to seek wealth, but merely to gain a subsistence, or to enjoy the freedom of the woods. They built their simple cabins and planted their crops of corn between trees which they killed by circling. Their greatest immediate problem was to live until the first crop was made, and here there was much difficulty.

The influx of immigrants was so great in 1816 and 1817 that the Indians and scattered pioneers were not able to furnish enough corn to meet the needs of the newcomers. In 1816 corn brought four dollars a bushel along the highway from Huntsville to Tuscaloosa, and was so scarce did this article become among the local Indians that the Government had to come to their rescue in 1817 in order to relieve actual distress. It is worth our while to know whence the various immigrants came into Alabama country; by what routes they reached their destination, and in what part of the territory they settled.

An interesting letter from Clabon Harris to General Jackson, Fort Claiborne, Jan. 12, 1816, gives an account of the conditions of some of the squatters in "The Jackson Papers."

"The Natchez Trace" into Mississippi Territory

The two roads through Mississippi Territory for which Congress made appropriations in 1806 were continuations of established routes of travel. From Nashville to Natchez the crossing of the Tennessee River at Muscle Shoals was known as the "Natchez Trace".

Actually, it was a continuation of the "Kentucky Trace" which passed from Nashville through Lexington, to Maysville, and thence by the Old National Road through Columbus, Zanesville, and Wheeling, then on to Pittsburgh. Following the general course of the Mississippi, the Natchez Trace was the principal highway for the region that it traversed.

This route was described as being hardly more than a bridle path through the woods that did not deserve to be called a road.

The highway along the route from Athens to New Orleans which followed the direction of the Alabama River and passed through the Tombigbee settlements came to be known as the "Federal Road."^^ Beyond Athens, the route passed northeastward through Greenville, Salisbury, Charlotte, and Fredericksburg, then on to Washington, Baltimore, and Philadelphia. Thus it traversed the piedmont region of the South Atlantic states and connected the Southwest with the commercial centers of the East.

The Route from Georgia into Alabama

Diverging from this route just beyond the Georgia line, another highway passed eastward of it and connected the Southern capitals which stood at the fall line of the rivers flowing into the Atlantic. Extending through Milledgeville, Augusta, Columbia, Raleigh, and Richmond, this again united with the piedmont route just before reaching Washington.

The Pittsburgh-Philadelphia Highway into Alabama

But there was still another means of access to the Alabama country which was of great importance. Diverging from the Pittsburgh-Philadelphia highway, this road passed southwestward through the Valley of Virginia, then followed the course of the Holston river to Knoxville. From Knoxville, the original highway passed westward to Nashville, but with the formation of Madison County, a spur was extended southward to Huntsville, and this soon came to be an important route of travel.

Two Choices of Roads into Alabama from Georgia

In 1818, a man coming into Alabama from the piedmont region of Georgia would have the choice of two routes. He could go by the Federal Road into the Alabama-Tombigbee basin or he could take a road which passed from Augusta to Athens, crossed the Tennessee River where Chattanooga now stands, and led on to Nashville.'" The highway crossed the road from Knoxville to Huntsville and gave access to the fertile Tennessee Valley region. The Georgia men who helped to settle Madison County in 1809 took this route.'" but the later emigration of Georgia planters was mostly into the southern part of Alabama, and they passed along the Federal Road.

The first lands of the Creek cession which were put on sale were disposed of at Milledgeville, Georgia, and they lay along the upper course of the Alabama River in the neighborhood of the later Montgomery County.'^ It is easy to understand, therefore, how it was that the Georgia planters established a predominance in this region from the first. With this as a nucleus, the immigrants from Georgia seem to have followed the route of the Federal Road and they came to form perhaps, the strongest element in the population of all the southeastern counties of Alabama.

South Carolinians into Alabama

Men from the piedmont region of South Carolina also had two routes open to them. They could take the fall-line road through Columbia or the piedmont road through Greenville and reach the Alabama basin by the Federal Road. But if they wished to reach the Tennessee Valley, they could pass northward from Greenville, through Saluda Gap in the Blue Ridge where it borders North and South Carolina, then to the site of Asheville, and along the course of the French Broad to Knoxville, and thence to Huntsville.^o Immigrants came by both of these routes, and, appearing to have avoided the settlements of those who preceded them in the Tennessee Valley and in the Alabama River basin, the majority of them passed on from both directions into the central hilly region or the basin of the Black Warrior and upper Tombigbee Rivers.

North Carolinians into Alabama

Men coming from North Carolina could have taken the route along the French Broad to Knoxville, and thence to Huntsville, but since this road traversed only the mountainous western re-region of the State, it is probable that most of the immigrants from North Carolina found the highway from Raleigh through Columbus and Augusta to the Federal Road more convenient. These men, like those from South Carolina, found the central region of Alabama most attractive.

Virginians into Alabama

The Virginians who came from the Valley followed their highway through Cumberland Gap and down the Holston to Knoxville, thence gaining access to the Tennessee Valley. Some of these passed on down to the Black Warrior and Tombigbee Valleys. For Virginians from the piedmont region, it was more convenient to take one of the eastern roads leading to southern Alabama, whence they could make their way into the Tombigbee-Warrior region if they so desired. The Tennessee Valley was most easily accessible to the men just over the line, and consequently, Tennesseeans had a predominance in this section. Some bought lands in the Valley, while others passed beyond into the hilly region and became squatters upon the National domain, for the lands in the valley were put upon the market principally in 1818, but those south of it were not sold for several years afterward. Here back-woods communities were established in the isolated valleys, and frontier conditions of life prevailed for a long time.

Tennessee to Alabama

The principal route of travel connecting the Tennessee Valley with the Alabama-Tombigbee region was a road passing southwestward from Huntsville through Jones Valley to the town of Tuscaloosa, which grew up at the head of boat navigation upon the Black Warrior. It was along this route that the principal settlements were made in the central hilly region.

At first, the Tennesseeans predominated here, but South Carolinians soon came in so numerously as to outnumber the Tennesseeans in some localities. The struggle for supremacy between these elements in Blount and Jefferson Counties provoked open hostilities before it was settled. Finally, the Tennesseeans came to predominate in Blount, while the South Carolinians had the majority in Jefferson County.

As in this case, most communities had their local color, and

In the Tombigbee-Warrior region, North Carolinians, South Carolinians, and Virginians mingled in varying proportions but together formed a predominating population element that had its own characteristics.

Populations

As late as 1856, Greene County, at the conjunction of the Black Warrior with the Tombigbee, had a population of 438 native South Carolinians, 357 Alabamians, 348 North Carolinians, 92 Georgians, 45 Tennesseeans, 24 Kentuckians, 12 men from Connecticut, 37 from Ireland, and 10 from German. The presence of a small number of foreigners is characteristic of the early period, and so is the presence of New Englanders. The cosmopolitan population was confined to trading towns where the merchants were mostly Yankees.

Germans

This was especially true of Mobile, where the transient population was turbulent and varied. A community of Germans was established at Dutch Bend on the Alabama River; and Demopolis, on the Tombigbee, was founded by a band of Napoleonic refugees. However, such segregated community-building was not characteristic.

Source: The Formative Period in Alabama 1815-1828 by Thomas Perkins Abernethy, Ph. D., Professor of History, University of Chattanooga.

Thanks so much for the additional information! Jeannette

What an interesting article! Thank you for putting it together.

Another relatively easy route into northeast Alabama was available to Tennesseans who settled in the Sequatchie Valley, about 20 miles west of the Tennessee River Valley and Chattanooga. My own ancestors lived in the valley on bounty land received for service in the Revolutionary War. These settlers lived in the counties of (north to south) Bledsoe, Sequatchie, and Marion. The 150-mile long and narrow Sequatchie Valley is part of the Cumberland Plateau. The Sequatchie River flows south-southwest from the southern part of Cumberland County, Tenn., through the counties named, to (today) a Tennessee River impoundment, Lake Guntersville. South of Guntersville, Ala., the name of the valley changes to Browns Valley, drained by Browns Creek. What's notable is how straight the valley is. Relocating from its northern parts south into Alabama, settlers must have felt they were merely following a continuation of the same geological feature, irrespective of any change in political boundaries.